A Mystery for All Seasons

A Mystery for All Seasons

A serial killer who, on holiday after holiday over more than a year’s span, kills one member after another of a prominent mafia family. A Gotham law enforcement establishment and a Caped Crusader anxious to stop this killer. A confounding mystery.

The distinction between literary and genre fiction could be compared to the distinction between sculpture and architecture. A literary story (whether eight or 800 pages in length) is intended to be a work of art, like sculpture. Sculpture need only provoke some reaction, intellectual or emotional, and it’s done its job—and of course, sometimes that reaction can be profound or even life-changing. Architecture, however, doesn’t get off so easy. A house–whether modular and identical to its twenty closest neighbors, or custom designed by Frank Lloyd Wright–first and foremost has to keep out the rain. It needs to have working toilets. The stove must generate heat to set pots a-boil. The same point could be made about genre storytelling, in whatever medium: it is expected to be functional. A Spider-man comic should excite and amuse. Horror must horrify. A mystery must mystify. It makes no sense to criticize a Gothic cathedral as less “artistic” than, say, Michelangelo’s “David” simply because of its functionality, because the cathedral has a roof, supporting pillars, and, “predictably,” doors and pews and stained-glass windows. The same could be said of calling a mystery “formulaic” because it involves a perplexing murder(s) and the solving of same. It’s in how the story’s done, in the inventiveness of plot, character, and setting, as well as language, that the artistry comes in.

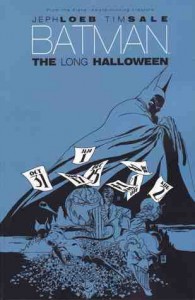

All of which brings me to The Long Halloween. In structure, this story is a mystery, rife with clues and red herrings, rather than a superhero story, and a well-told mystery at that. The Long Halloween defies the television- or parlor-mystery convention of what Aristotle called “unity of place and time”; this story stretches out over the course of more than a year. Its one-murder-per-holiday structure, though, gives The Long Halloween a variety of flavor, of season, of mood, that keeps chapter after chapter fresh, with some great twists and turns along the way. Each chapter, of course (since The Long Halloween was originally released serially) has to have its own plot, its own internal tension and suspense, all of which play into the overall story arc—no simple feat, but Loeb makes it look easy here.

In superhero stories, there’s sometimes a temptation to throw too much of our hero’s rogues’ gallery at him/her all at once—second and subsequent movies in superhero franchises are most guilty of this, usually resulting in the crashing and burning of said franchise. (I’m still dumbfounded that someone felt the Joker in The Dark Knight, especially as Heath Ledger played him, just wasn’t villain enough to carry a movie, and that tacking on a two-bit Two-Face plot would somehow improve the story.) The Long Halloween plays this game too, but because of the scope of the story, and because it’s a mystery, where having numerous suspects is essential, there isn’t that too-many-villains-crammed-into-the-bus feeling that sometimes happens. The Joker here, for example, may not be the scariest of all Jokers, and Calendar Man isn’t particularly frightening in his Hannibal Lector role, but that’s not the point; they play their parts perfectly as functionaries in building the suspense and the momentum of an engaging and memorable mystery. On top of this, the combination of Tim Sale’s artwork and Gregory Wright’s coloring evoke both character and mood more potently than any other Batman story I could name. Well worth the read, and for a writer, The Long Halloween is an object lesson in the right way to do it.